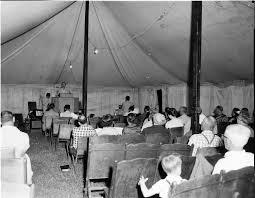

In the Summer of 1949 sounds of homespun music, clapping hands and shouts of Amen ascended into the night at the north end of our town. A tent meeting was underway.

Things about tents fascinate me. My mother-in-law’s Danish mom – Grandma Sadie – called up memories as a settlers’ daughter. People from Denmark are evidently tough. The family spent their first winter in Montana living in a tent. Sadie’s beguiling reflection, “but it was a pretty mild winter” prompted a reflection of my own; ‘there can be no such thing as a mild winter in Montana – in a tent.’

In my adult years, while living in a tropical region, I bought a weathered six-man camping tent. A patch in the roof presumably marked the spot where the tusk of an elephant punctured the dwelling. The agitated mammal, I was told, raised the edge of the tent off the ground before moving on.

In the ‘1940s and ‘50s open tents seated fifty to a hundred people and served the purposes of transient American preachers. Our visiting preacher, a lady minister oversaw with the aid of her husband, the tent’s inauguration on a vacant lot. A sawdust floor, wooden folding chairs, worn hymnals and a guitar or perhaps accordion completed the setting. The tent’s older visitors kept hand-held fans in easy reach. The preaching was Bible-centered, the messages vigorously delivered, the singing pulsing with strength.

Clyde and Thelma began attending the meetings with my sister, brother and me in tow. The music, preaching and testimonials seemed to usher in the Presence. The family never tired of experiencing the nearness of God in the company of other Jesus followers.

After a few weeks of conducting meetings the minister and her husband felt drawn to remain in our Northeastern Oklahoma town. They rented a vacant building. The Living Way Tabernacle became our church home.

After the polio experience my left leg was fitted with a knee to shoe brace. In my fifth year the brace came off for good. I was active without it and, lacking the benefit of therapy coaches in that era, my folks simply retired the brace. My limp became a little more pronounced from that time.

Support structures and supportive people. Good things to have in our lives. They are wonderfully provided (some would say from above) to help meet real needs, to make up the lack. It’s true that personal betterment can sometimes actually be hindered through over-support. That is, when a kind of assistance or a certain level of it is no longer appropriate.

Still, help is needed by all of us, through all of life. Different types of help and in differing amounts, for different seasons. Prematurely withdrawing support (as with braces) may damage or hinder progress along a road to wellness. Or, at least, better mobility.

I fell in love at age five. Her name was Opaline. She was beautiful. Even in braces. . Especially in braces.

©2015 Jerry Lout